It’s been a month since Maria Sharapova announced her retirement from tennis. With the coronavirus pandemic taking precedence, there hasn’t been much time to truly analyse the four-time Grand Slam champ departing. So without further ado…

It was inevitable. Many expected it to happen four years ago, but she revealed the news in the typical Sharapova way: a first-person article published by Vogue and Vanity Fair.

For as long as I can remember, Sharapova departing tennis before many of her peers seemed a likely possibility. Whether that was through persistent injury issues, inconsistencies in Grand Slam tournaments or how she was exposed for having just one plan on-court, longevity and success in any sport is difficult for injury-prone athletes.

A part of her retirement piece read:

“Tennis – I’m saying goodbye. I’ll miss it everyday, the training and my daily routine, my team, coaches, moments sitting with my father… handshakes – win or lose and the athletes, whether they knew it or not, who pushed me to be my best.

My path has been filled with volleys and detours but the views from its peak were incredible. After 28 years and five Grand Slam titles though, I’m ready to scale another mountain – to compete on a different type of terrain.”

As New York Times’ journalist Chris Clarey described during a Tennis Podcast interview last month, the 32-year-old said she was in pain and had been struggling physically. That was common knowledge. The extent of her issues though, was not.

“We talked for almost two hours. No cheers, a lot of wincing, I hadn’t realised to what degree she had been struggling physically. Poised under pressure, very decisive and a clean break: it’s time to move on.”

– Clarey on his interview with Sharapova

When you break it down, 32 seems like an increasingly younger age to bow out. For context, ATP’s big three are all there or even older. Novak Djokovic, the youngest, turns 33 next month. Roger Federer (38) leads the way, while Rafael Nadal turns 34 in June.

At the time of writing, there are seven women 30 or older in the WTA’s top 50. Stretch it to #100, you get eleven more. With the exception of big sister Venus, world number nine Serena Williams (38 years, 5 months) leads the way despite being the oldest – showing it’s not impossible if you’re physically capable of maintaining those high levels over time.

Petra Kvitova (30) and Angelique Kerber (32y, 1m) are just two Grand Slam champions who’ll find themselves in a similar position to Sharapova, though whether that happens soon or much further into this decade remains to be seen.

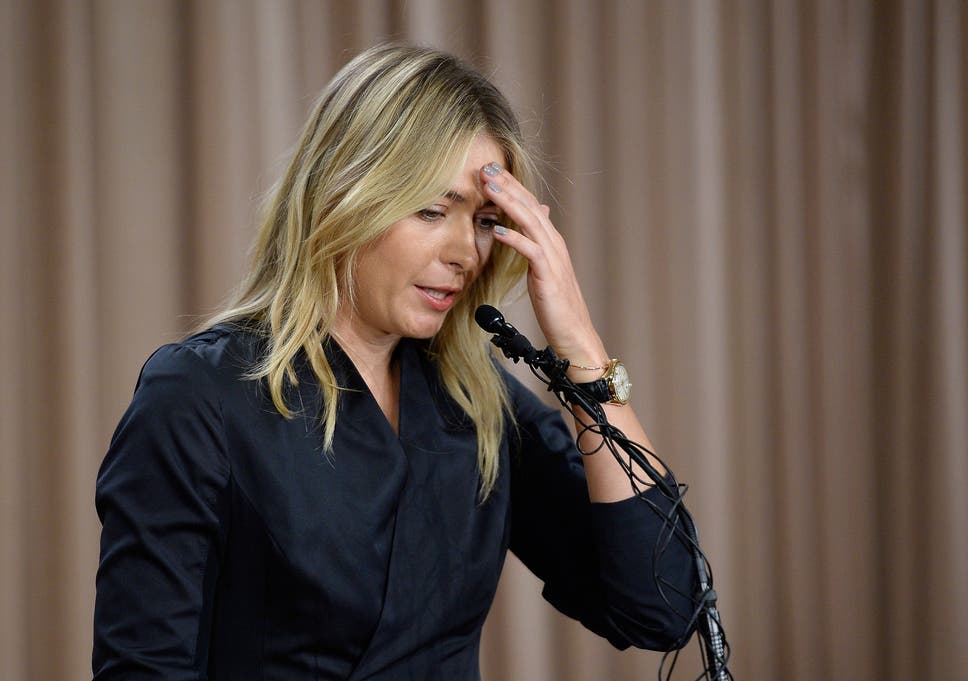

Addressing the unforgettable meldonium scandal

Sharapova’s meldonium admission, courtesy of a press conference she called to address the situation saw her receive a two-year suspension, which was reduced to 15 months.

The scandal actually prolonged her career as she was defiant in wanting to silence critics and prove a point while doing so – even with her body continually breaking down.

Ultimately though, it left an indelible mark on both her legacy and reputation, especially after the drastic performance drop-off having returned in 2017.

Sure, she suffered with injuries and form but the fact she only won a solitary title in the three years afterwards suggests it was helping her more than she’d ever readily admit.

It is said to increase blood flow, which improves exercise capacity in athletes. She was warned multiple times in the months before it was placed on the banned list, so why didn’t she do something prior to testing positive at the Australian Open in 2016?

That being said, I believe only she knows whether she purposely cheated or not.

Call it wishful thinking or naivety on my part if you will, but the fact she’d been taking it since 2006 – a decade – and findings continue questioning whether the drug truly has any performance enhancing elements, just speaks volumes. High-level incompetence? Undoubtedly. Guilty as charged? It’s not simple and the answer depends on who you ask.

What have tennis experts said?

Chris meanwhile, echoed similar beliefs on how she’ll be remembered and whether she cheated knowingly: “It certainly is a blot on the copybook, no question about it. She made a big mistake, as professional as she is, should have known what was going on and taken ownership of that, had people around her to be careful about it.

I don’t believe she’s an intentional doper and has paid a high price for it, personally and her reputation. You look at comments [from his article]: doper, cheat, good riddance, yes she can’t be viewed in the same way as someone who never did, but it’s not like her whole career is a sham because of an administrative error.”

Contrastingly, Catherine Whitaker said: “For me – I’m aware this is unfair – she’s more tainted by my knowledge that she was legally doping for all those years, rather than by the administrative error, which led to her testing positive and receiving the ban.

It’s unfair because they [other tennis players] might have all been taking meldonium their whole careers, up until it was put on the banned list and she was exposed for it. I’m aware that’s an unfair position to be in, it’s unfortunate but I’m uncomfortable and although not naive to the fact it goes on, it [the act of cheating] depresses me.”

The main problem with instances like this is being able to separate fact from opinion. The truth remains: she tested positive for a banned substance and was consequently punished for doing so – even though it’s not regarded as doping, it was against the rules.

Players themselves had contrasting views on the situation, with many strongly against her proposed return while some like Novak sympathised without actively coming to her defence. Regardless of what you believe, it’s a grey area no-one is comfortable discussing.

Her lasting legacy, memories and my thoughts

It should come as a surprise that the one Grand Slam she won more than once in her career, was the one she described herself as a ‘cow on ice’ in, at Roland Garros.

But as a player with her share of limitations – not quick, a weak forehand and preferring shorter points as a result – she still managed to utilise her strengths and at her best, was relentless from point-to-point, something Rafael Nadal is notorious for.

She won five Slams over ten years, which goes to show there wasn’t one stint packed with consistency and instead she emerged victorious with more success to her credit.

This coronavirus pandemic has taken centre-stage, which means all sport – tennis included – will have a weird feel once action resumes. By the time we see live tennis again worldwide, players would have aged and because careers have been unexpectedly halted, many would have already forgotten about Sharapova’s departure.

When you strip all of the nostalgia aside, the retirement announcement felt out-of-the-blue but just because it was coming doesn’t mean she won’t be missed once the sport returns.

That she decided to announce retiring via Vogue says a lot, as she often compartmentalised her emotions. Naturally, behaving this way made it harder for tennis fans to support or like her as a person, even if she meant well. Eager to avoid giving anyone a psychological edge they could benefit from, it’s understandable.

Just how good was she?

It’s easy to overlook how good she was, because she didn’t win a whopping number of Slams yet had a blossoming career off-the-court – most are not lucky enough to replicate.

Chris said it best: “She was this twig, a twiggy talent with the heart of a lioness – playing every ball like it was going to be her last. To do what she did [against Serena], on that occasion at that level, she just seized it.

People say she got to where she did because of looks, how she managed herself, there’s some truth in that but you can’t forget the breakthrough moment was that match – beating the world’s best player, which is why she used that platform and leverage.”

A 17-year-old girl beating the world’s best player is no mean feat, but to do so in a Wimbledon final and break numerous records on such a big stage, speaks for itself.

It’s perhaps why there was such pressure and focus on making a Serena-Sharapova rivalry in the years that followed, even if their H2H record (20-2) showed anything but.

Good groundstrokes and a 6ft 2in frame which blessed her with a reliable weapon as far as serving was concerned, the 2008 Australian Open was the peak of her powers. One can only wonder how things would have been, if not for persistent injuries.

Ultimately though, her body failed her when she needed it most as Serena enjoyed a revival back to the top and younger players began emerging on the scene too.

In the later years of her career, it got to a stage where she was worrying about how she was feeling during matches: her shoulder, forearm, being scared of sustaining injury and it almost sparked an internal dialogue when on-court.

Since then [returning in 2017], Maria has dealt with recurring tendon damage in her right shoulder and inflammation in her forearms that at times has made it excruciatingly difficult to even grip a racket, much less rip a forehand.

Three first-round Slam losses is not an ideal way to go out, but her weaknesses have only magnified with age and it had got to a point where she no longer had anything to prove.

How will she be remembered?

Chris described her as a street fighter that resembles a model, while I think she was a defiant operator who fans loved to hate. I wanted a third opinion, so spoke to tennis expert Richard Phelps (_richardphelps), to get his thoughts:

MO: Having just retired, how do you think she’ll be remembered in history?

RP: I think she’ll go down as one of the best female players of the 21st century, bar Serena. I think only her, maybe Venus and Justine Henin’s achievements outrank Maria. Off-the-court troubles [drugs ban] have tarnished her reputation in some people’s eyes and made her a controversial figure but I don’t think it should detract from her career.

MO: Is she another what if? Considering the potential she had, and how injuries/inconsistency let her down in Slams?

RP: I don’t think she’s another what if case, as she won a lot more than most others did in her era. But yes, her injury record and ban later on didn’t help when it came to being more consistent at Grand Slams. With the raw potential she showed by winning Wimbledon in 2004, I think it’s fair to say she underachieved despite being world no.1 on multiple occasions and winning five Slams with runners-up honours in five more.

I think it’s more to do with how dominant Serena was over the 15-year period and Maria’s inability to defeat her after the mid-2000s. I liked her though: she was a fierce competitor, one of the toughest the game has seen in recent years and I think people will remember that about her too.

She was more than a tennis player, her name is a global brand and she won the third-highest money in WTA earnings’ history, while amassing a huge fortune from numerous endorsements.

MO: What’s your most memorable match or instance involving her?

RP: The 2017 US Open, her first since the ban was lifted, sticks out to me. Drawn against Simona Halep in R1, many thought she wouldn’t stand a chance, but she loved playing at Flushing Meadows – especially under the lights on Arthur Ashe for a night session. Maybe it allowed her to show off both her ability and celebrity status in-front of other famous high-rollers in New York, but she defeated Halep during a terrific encounter.

That meant at the time, she was still undefeated in night sessions on Ashe. She won 23 of her 25 matches in that stadium at night-time, gave an excellent post-match interview and received a great reception from the crowd, who I think she won over thanks to the effort she put in during the match.

She always spoke so well and seeing her stand in the middle of the court, victorious on the big stage, in a custom-made Nike dress with Swarovski crystals on it perhaps sums Maria Sharapova up best.

So, what’s next for Sharapova?

She is said to have all kinds of plans, with side businesses and other things to be focusing on – including her candy business Sugarpova.

Maria also wants to study architecture at university level, is keen to design and improve tennis facilities while remaining involved in Nike with design elements among other things.

Her boyfriend is art-based and she’s shown an interest in wanting to help with that too, while also being there for family and friends that hasn’t been possible during her professional career.

The coronavirus pandemic is naturally having an impact on everyone worldwide, but Maria will see these next few months as valuable time to focus her energies on other projects out of the limelight.

Many thanks to Richard and indirectly the Tennis Podcast for helping me with this piece. As I mentioned earlier, I felt it was important to set aside time to write it properly: Sharapova and her retirement is a delicate subject so it wouldn’t have been complete without other contributing voices, whether through my own questions or their own thoughts.